LA SALLE'S TEXAS SETTLEMENT. René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, established a French settlement on the Texas coast in summer 1685, the result of faulty geography that caused him to believe the Mississippi River emptied into the Gulf of Mexico in the Texas coastal bend. The settlement on the right bank of Garcitas Creek in southern Victoria County has been called Fort St. Louis, but in fact it had no name, only a description. La Salle himself referred to it as "the habitation on the riviére aux Boeufs [Buffalo River] near the baye Saint-Louis."

The precise location, about five miles above the Garcitas creek mouth in Lavaca Bay, has long been in dispute, despite a preponderance of evidence favoring the actual site, presented by Eugene Herbert Bolton as early as 1908. The site was confirmed in June 1996 with the excavation of eight French cannons. Buried there more than three hundred years previously by Spanish general Alonso De León, the cannons provided the impetus for excavation of the Keeran Ranch site (1996–2002) by archeologists of the Texas Historical Commission. This project confirmed that the Spanish Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía Presidio was built on the La Salle settlement site early in 1722. Spanish soldiers led by Domingo Ramón had occupied the site the previous year. Of an astonishing total of 157,726 artifacts recovered from the site, approximately 10 percent are of French provenance, the remainder being of Spanish and Indian origins.

La Salle's Expedition to Louisiana in 1684, painted in 1844 by Theodore Gudin. La Belle is on the left, Le Joly is in the middle, and L'Aimable is grounded

La Salle's Expedition to Louisiana in 1684, painted in 1844 by Theodore Gudin. La Belle is on the left, Le Joly is in the middle, and L'Aimable is grounded

The Settlement

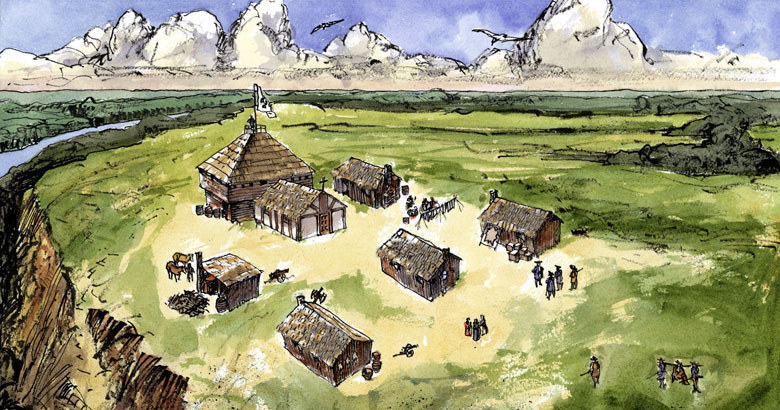

In February 1685 La Salle had landed 180 colonists at Matagorda Bay in Spanish-claimed territory. That number included half a dozen young women, two families with a total of seven children, and several youths scarcely out of their teens. The first house to rise on the Garcitas creek bank was a two-story structure of four rooms, built of hewn logs and timbers salvaged from La Salle's wrecked supply ship, Aimable. The roof was of the ship's planking covered with buffalo hides. Although this "main house" served as a lookout post, it was never considered a fort. Recent artists' portrayal notwithstanding, it is nowhere described in the historical record as a blockhouse. Five other houses, quarters for the colonists, had walls of vertical stakes set side by side in the ground and plastered with mud. Roofs were of buffalo hides or thatch. One of these was a chapel, the scene of the first Catholic religious service held in Texas outside the El Paso area. The first European child of record born in Texas is believed to have been christened there.

The grueling labor of establishing the colony, combined with exposure, disease, bad treatment, and poor diet, reduced the number of colonists by more than half within six months. From October 1685 to January 1687 La Salle left the colony on three occasions to explore his surroundings. During his first long absence—a journey to the west—his one remaining ship, Belle, was wrecked in Matagorda Bay, leaving the colony marooned. On his final departure, supposedly to seek rescue from his Fort-Saint-Louis-des-Illinois, he left twenty-three men, women, and children, in the colony of six crude structures. The expedition's historian, Henri Joutel, on leaving the settlement with La Salle, declared, "there was only the house . . . , having eight cannon at the four corners, unfortunately without cannonballs," and "when we left, there was nothing else in the nature of a fort." As Joutel reveals, there was never a palisade.

Robert de La Salle, also called Robert Sieur de la Salle, was a famous French explorer. He was born on November 21, 1643, in Rouen, France.

Robert de La Salle, also called Robert Sieur de la Salle, was a famous French explorer. He was born on November 21, 1643, in Rouen, France.

"Fort St. Louis" does not appear in any of the accounts by participants in the Texas episode. The spurious journal of La Salle's brother, Abbé Jean Cavelier, as it was recast by the Marquis de Seignelay after Cavelier's return to France, referred once to "the Baye or fort St. Louis." Jean Michel, in his 1713 abridgement of Joutel (as it appears in English translation), seized this verbiage to assert that "the dwelling," like the neighboring bay, was given the name of "St. Louis."

Waiting for Rescue

For two years those left at the settlement, now in the charge of Lieutenant Gabriel Barbier, held on to the hope of rescue as they waited in vain for word from the "rescue mission." Gradually, as it became apparent that no help was coming, their hope faded. It probably was during the twelve-day celebration of Christmas, 1688–89, that the Karankawa Indians approached the settlement in the guise of friendship then fell upon the inhabitants in murderous frenzy. The massacre was complete except for the children, who were taken by the Indian women and lived among the Karankawas until they were rescued by the Spanish expeditions led by Alonso De León and Domingo Terán de los Ríos. One of the children was Jean-Baptiste Talon, age ten at the time (see TALON CHILDREN). It was he who, years later, provided the only eye-witness account of the massacre.

Of particular interest is the fate of Madame Barbier, one of the young women of the colony, who had married Lieutenant Barbier. The Indian women took her, with her babe at breast, to their village. When the warriors returned, they killed Madame Barbier, then held the baby by its heels and bashed its head against a tree. Neither the name nor the gender of this infant, the first European birth of record in the present state of Texas, is known (see BARBIER INFANT).

The Result

The expedition that was to bring aid to the colonists, meanwhile, had fallen apart in the East Texas wilds scarcely two months after leaving the settlement. Five men died in the bloodletting as Frenchman turned against Frenchman. La Salle himself fell, the victim of an assassin's bullet. Others deserted to live among the Indians. Eventually, five men reached France—including Joutel and Abbé Cavelier—much too late to send help to the colonists.

Situated on a high point on the banks of Garcitas Creek, the small French settlement later to be known as Fort St. Louis consisted only of a two-story building made of salvaged ship timbers, a chapel, and some small jacal structures. Crudely built with roofs of thatch, the huts offered little protection from the natural elements and even less from the Karankawa.

Situated on a high point on the banks of Garcitas Creek, the small French settlement later to be known as Fort St. Louis consisted only of a two-story building made of salvaged ship timbers, a chapel, and some small jacal structures. Crudely built with roofs of thatch, the huts offered little protection from the natural elements and even less from the Karankawa.

Resource: The Hanbook of Texas - La Salle's Texas Settlement