CRASH AT CRUSH. A plaque fifteen miles north of Waco in McLennan County marks the site of the "Crash at Crush." On September 15, 1896, more than 40,000 people flocked to this spot to witness one of the most spectacular publicity stunts of the nineteenth century-a planned train wreck. The man behind this unusual event was William George Crush, passenger agent for the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad. In 1895 Crush proposed to Katy officials that the company stage a train wreck as an attraction; he planned to advertise the event months in advance, sell tickets to transport spectators to and from the site on Katy trains, and then run two old locomotives head-on into each other. The officials agreed.

Throughout the summer of 1896 bulletins and circulars advertising the "Monster Crash" were distributed throughout Texas. Many newspapers in Texas ran daily reports on the preparations, and some papers outside the state carried the story. As Crush had predicted, the Katy offices were flooded with ticket requests. The engines, Old No. 999, painted a bright green, and No. 1001, painted a brilliant red, were displayed in towns throughout the state. Thousands turned out to look at them.

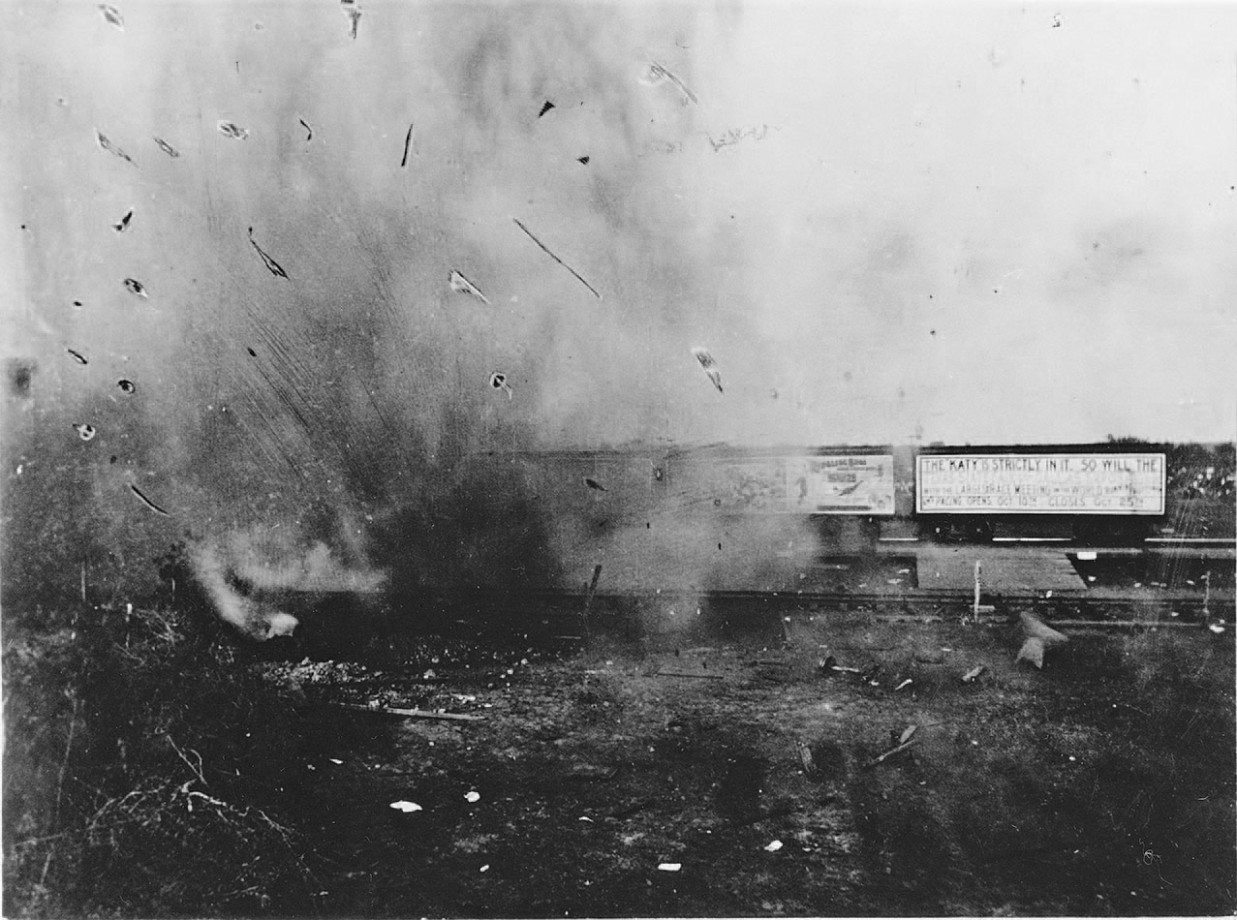

Almost simultaneously, both boilers exploded, filling the air with pieces of flying metal.

At 5:00 P.M. engines No. 999 and 1001 squared off at opposite ends of the four-mile track. Crush appeared riding a white horse and trotted to the center of the track. He raised his white hat and after a pause whipped it sharply down. A great cheer went up from the crowd as they pressed forward for a better view. The locomotives jumped forward, and with whistles shrieking roared toward each other. Then, in a thunderous, grinding crash, the trains collided. The two locomotives rose up at their meeting and erupted in steam and smoke. Almost simultaneously, both boilers exploded, filling the air with pieces of flying metal. Spectators turned and ran in blind panic. Two young men and a woman were killed. At least six other people were injured seriously by the flying debris.

The collision of the two trains at Crush, Texas. Note that the text reads, in part, "Indications are that the boilers exploded after the trains had collided and the cars had stacked up."

The collision of the two trains at Crush, Texas. Note that the text reads, in part, "Indications are that the boilers exploded after the trains had collided and the cars had stacked up."

The Katy wrecker-trains moved in to remove the larger wreckage, and souvenir hunters carried off the rest. People began to leave for home, the tents, stands, and midway booths came down, and by nightfall Crush, Texas, ceased to exist. The Katy quickly settled all damage claims brought against it with cash and lifetime rail passes. As for George Crush, the railroad fired him that evening but relented and rehired him the next day. He continued to work for the Katy until his retirement. Composer Scott Joplin commemorated the event in his march Great Crush Collision which was published just a few weeks after the wreck. It has been surmised that the spectacle drew its huge audience in part because it occurred at a time of economic distress when railroads symbolized to many the evils of the big business "octopus" and were a target of attack for populist politicians.

Despite the death of two observers, spectators rush to the scene of the crash hoping to acquire pieces of the wreckage as souvenirs.

Despite the death of two observers, spectators rush to the scene of the crash hoping to acquire pieces of the wreckage as souvenirs.

Resource: The Handbook of Texas - Crash at Crush